A Educação

on-line é uma realidade ao alcance de muitas pessoas interessadas em aprender

sobre algum tema específico e sem qualquer custo. O site Coursera oferece cursos (em

inglês) em diversas áreas, inclusive na área de humanas, de alto

nível. As aulas são bem preparadas, organizadas em pequenos módulos para

que se possa assistir sem serem cansativas.

Tem a duração de cerca de 2 horas

semanais que podem ser divididas dia a dia em pequenos vídeos de poucos

minutos. Há exercícios para serem feitos que serão corrigidos on-line, na

mesma hora que são enviados ou, ainda, serão revisados por um dos colegas

de "turma". Os cursos são oferecidos pelas melhores

universidades dos Estados Unidos e com professores reconhecidos por sua ótima

didática e conhecimento. Para os que não conseguem acompanhar as aulas em

inglês há diversos cursos com legendas em espanhol. Para os que compreendem

um pouco do idioma podem ser acionadas as legendas em inglês ou mesmo reduzir a

velocidade da fala. A ideia é muito boa. Seria ótimo que tivéssemos alguns

cursos em português ou com legendas em português.

Outro site bem interessante é o Veduca.

Neste há aulas de universidades de todo mundo, inclusive do Brasil - a

USP. Para algumas aulas já há legendas em português, porém ainda não para todas

as aulas. É interessante assistir aulas de temas que não temos qualquer conhecimento

prévio e poder compreender as noções básicos de assuntos interessantes. Você

faz seu horário e é divertido interagir nos Foruns de debates entre os

inscritos.

O futuro na educação está presente!

How Coursera, A Free Online Education Service, Will School Us All

An online education outfit started by a pair of Stanford

professors is offering top-drawer college-level courses

for free. Higher learning may never be the same.

professors is offering top-drawer college-level courses

for free. Higher learning may never be the same.

Christos Porios, 16, lives in Alexandroupolis, a small Greek city on the Aegean Sea about 20 miles from Greece's eastern border with Turkey. "My mother's a teacher and my father's a mechanic," he explains, adding that neither is particularly knowledgeable about computers--especially compared with him. For years, he's had free rein over the family PC, and he's taken advantage of the time to teach himself programming. Mainly, he uses sites like Wikipedia, YouTube, and the Khan Academy--a portal with thousands of short, free educational videos. "Yes," says Porios. "I would call myself a geek."

"AT FIRST THEY WERE LIKE, 'YOU CAN'T LEARN ANYTHING THAT WAY.' BUT THEY SAW I WAS GETTING SERIOUS. I WAS LEARNING STUFF, AND I LIKED IT. THEY REALIZED THAT 'REAL LIFE' INCLUDES THINGS LIKE MACHINE LEARNING."

Last fall, as the Greek economy spiraled toward default and rioters filled the streets of Athens, Porios was glued to his computer, but not to follow the eurozone crisis. He was taking a free class in machine learning offered by Andrew Ng, a professor at Stanford University, over an online platform Ng developed with his colleagues. Machine learning is an emerging discipline of computer science that deals with the analysis of very large data sets. Porios found the class riveting. His parents were perplexed to see their son rush home from school to sit for hours in front of the computer. "At first they were like, 'You can't learn anything that way,' " Porios recalls. " 'You should be paying more attention at school, at your real homework, at your real life.' " But after a few weeks, they came around. "They saw I was getting serious. I was learning stuff, and I liked it. They realized that 'real life' includes things like machine learning." Drawing on what he learned, Porios was able to participate in the International Space Apps Challenge, a virtual hackathon using data from NASA and other government agencies. He also began to "play with" data sets he downloaded from the World Bank website.

If one teenager in one small city in Greece can become a genius hacker through an online course, does it mean the world has changed? We have been hearing about the disruptive potential of online education for at least a decade now. Yet over the past six months, online ed has taken a giant leap forward. A number of new, high-profile ventures feature professors from elite universities offering free courses online. All of these courses have video and social-networking components. All have attracted millions of dollars in funding. And perhaps most significantly, all have drawn initial enrollments of at least six figures. Ng's course in machine learning, the one that Porios rushed home from school to watch, attracted 104,000 enrollees around the world. Ng was amazed. "It would take me 250 years to teach this many people at Stanford," he says. And so, just one month into the course, Ng and his Stanford colleague, Daphne Koller, decided to leave their tenured faculty posts and dive into online teaching full-time. In April, they launched their company, Coursera, with a $16 million round of venture funding. The backers include John Doerr at Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers and Scott Sandell at New Enterprise Associates.

Doerr et al. will have to wait a while before they recoup their investment. Like a lot of online enterprises in their early days, Coursera has captured lots of eyeballs but not, as yet, any revenue. If it does start making money, it is unlikely to have the field to itself. Still, Coursera has some advantages that leave it well positioned. It is the first to offer top-drawer courses in humanities and the social sciences, a particular bugaboo for online learning in the past. It has also managed to team up with more colleges than any of its rivals--a total of nine, announced this spring and summer, including Princeton, Michigan, and the University of Pennsylvania.

The most intriguing aspect of the Coursera endeavor, however, is how quickly it promises to expand beyond a niche audience. All of the factors pushing Coursera and its competitors toward the mainstream of higher education are now crashing together. For starters, the newly minted knowledge-based economy is hitting a global slowdown, causing a spike in demand for higher education as people seek to retrain. This demand is running smack into the reality of the escalating costs of going to college and the attendant rise in student-loan debt, fueling anger and desperation among students (and demonstrations from Chile to Quebec) and trepidation in parents. The technology has changed, too. Broadband access is growing even in poor and middle-income countries, making online education both easily accessible and far more functional. At least 600 million people now have the ability to stream video, compared with only 300 million in 2007. "I think the potential impact is huge," says Michael Horn, who coauthored a book on change in higher education with Clayton Christensen, the father of disruptive innovation.

To Ng and Koller, Coursera's mission is simple and yet absurdly grand: to teach millions of people around the world for free, while also transforming how top universities teach.

And their business model? Well, they haven't quite figured that part out yet.

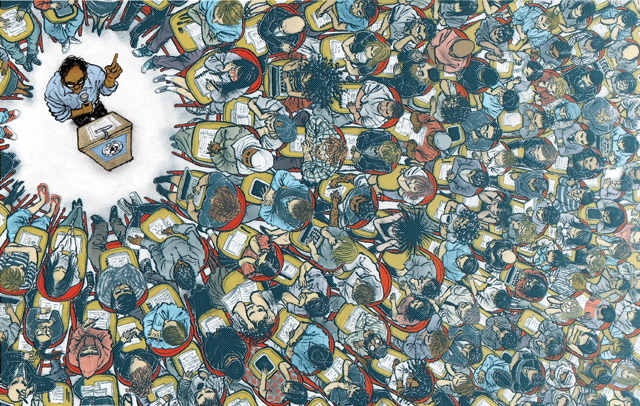

The face-to-face lecture dates back a thousand years. It still consumes hours of class time at even the best universities, and it doesn't scale up well. The lecture hall might be suitable for attending to a charismatic orator, but most learning benefits from give-and-take. And the greater the number of students in the room, the lesser the chance for interaction and, hence, for education in the classical sense of the term--educere, to draw out. As Koller, the Coursera cofounder, puts it: "When you're giving a lecture and you stop to ask a question, 50% of the class are scribbling away and didn't hear you, another 20% are on Facebook, and one smarty-pants in the front row blurts out the answer and you feel good." Koller and Ng believed they could solve the problem by doing something different online. "Why not take the 75-minute lecture," Koller asks, "break it up into short pieces, and add interactive engagement into the video so that every five minutes there's a question?"

In other words, Coursera's approach is a long way from a simple online video lecture. Consider Porios's experience. At home in Greece, he would watch Ng, sitting in his office in Palo Alto, work an example of matrix multiplication. Porios would then have to answer a few quick comprehension questions, and the program would tell him instantly if his answers were right or wrong. Ng and Koller have drawn on neuroscience research showing that exercises in instant retrieval enhance memory and comprehension more than complicated questions for later study. "This way," Koller says, "every single person needs to answer the question and retrieve the information."

Coursera courses are 6 to 10 weeks long, with an hour or two of videos per week. In addition to the snap quizzes, they feature weekly exercises, ranging from problem sets to spreadsheets to design projects or essays, and sometimes a final project or exam. For all quantitative courses, the platform uses artificial intelligence to evaluate each longer exercise, with instant results. Students can keep trying until they get the right answer. For humanities courses, Coursera is testing a form of peer grading.

Having thousands of other students taking the course at the same time is crucial, too. Students can find each other in the Coursera forums, where they have spontaneously formed study groups by native language or time zone. Though not the same as a chat over coffee, the virtual study groups can be effective and even (according to some students) surprisingly intimate. "Andrew Ng is the best teacher I've ever had, even though I've never met him," Porios says. "He was explaining the material very clearly, answering every single one of my questions only seconds after they came to my mind. It was like telepathy." If Porios had a question that the professor didn't address, he asked a fellow student. During the first round of Stanford open courses, students responded to one another's forum posts in an average of 22 minutes.

Those results are one reason that Ng and Koller are so optimistic about Coursera's potential. The two have been friends for 13 years, dating back to Ng's grad-student days at Berkeley. They moved from their old Stanford work space this May to a spartan and anonymous '80s-style, low-rise office park on El Camino Real, the main artery of Silicon Valley. The two make an intriguing contrast. The lanky Ng, self-effacing and approachable, was born in the United Kingdom and raised in Hong Kong and Singapore. Koller, who was born and raised in Israel, is more intense and abstracted, with a piercing gaze. Since emigrating from Israel and earning her doctorate at Stanford in 1993, she has specialized in the study of how to analyze large volumes of complex information. In 2004, while working to unlock the secrets of the human genome, she earned a MacArthur "genius" grant.

About four years ago, Koller recalls, she had become interested in how artificial intelligence might be used to improve student engagement. At around the same time, Ng was building a software platform for online courses. He used a simple setup that would let professors make videos of themselves while they marked up course notes with a tablet and stylus, as if in front of a blackboard. The two started to talk. They agreed on the potential of combining these technologies in new ways, both to personalize learning and to lower its cost of delivery.

And then, one Saturday last October, Koller and her husband, Dan Avida, a venture capitalist, were having lunch at the home of their friend Scott Sandell, the New Enterprise Associates VC, and his wife, Jennifer, a teacher. The couples' school-age daughters were running around playing. The wives were deep in conversation. The men were assembling the meal.

"You know, Daphne's working on something really interesting," Avida told Sandell. "But I don't want to interrupt our visit. Let's make a plan to talk later."

"The way our schedules are, that could take months," Sandell countered. "Why don't you both tell me about it now?"

So over bagels and lox, Koller explained that four weeks earlier, she, Ng, and a few other teachers at Stanford, as part of an official university project, had announced open online classes in machine learning, artificial intelligence, and programming. Each class, she added, had drawn more than 100,000 registrants.

Sandell recalls that he felt a thrill in the pit of his stomach. With a failed education startup on his record, he'd been on the lookout for a solid education-technology investment since he became a VC in 1994. "The rate of adoption made it obvious to me," he says. Before the plates had been cleared, he told Koller he wanted to invest.

Over several weeks in April and May, I interviewed about a dozen Coursera students around the world, via Skype, to get a sense of their goals and motivations. I also signed up for a Coursera course, Computer Science 101, to see how it actually felt to be a student on the platform. Many enrollees, like Porios, were following their scholarly passions. Others were looking to change jobs or start or expand a business. Sometimes they were doing it just for fun. One afternoon, I spoke with Sophia Naide, a 13-year-old eighth grader in northern Virginia, who was taking the computer-science course along with her mother. "I just think it's really amazing how you can learn literally any topic for free," she said, grinning through her braces.

True, these students aren't typical. Of the initial 104,000 people in Ng's machine-learning course, only 46,000 completed any assignments, and only 25,000 did a majority of the homework. (That attrition rate is similar to what you see in many for-credit, fee-based online courses.) So only a fraction of those who sign on for the coursework are demonstrably engaged with it. And yet, that fraction comprises an enormous number of people--which could grow far greater as word gets out.

The test for Coursera will be to find the right niche in the student populace. Challenging courses like Ng's in machine learning clearly draw the most serious and self-motivated students, many of whom are driven to further their careers. Kenji Kawaguchi, a 23-year-old nuclear safety engineer in Tokyo, signed up for Ng's course at the same time as Porios. He and a friend who works in web advertising took the course together, munching ham sandwiches and swigging black coffee at a local cafe. "Right now, I'm just an engineer doing risk analysis," he says. "But in the future, I want to be a researcher directing projects, so that's my motivation to keep learning."

The machine-learning course also reeled in Andy Rice, 33, who leads product management for a Wisconsin-based company that does weather forecasting for businesses. He tells me he "suggested" that more than 10 of his employees take the course (which they did) and that the company's predictions have since improved. More curiously, when Rice had an open position in the spring of 2012 for a mathematical scientist, more than 25% of the resumes he saw listed Ng's course. He sees them as people who want to stay on top of the industry. "I definitely want to hire people who are always questing for new knowledge," he says, "because life's not about what you learn when you're 22."

That seems especially true if it means switching out of the career you trained for at 22. Dennis Cahillane, a 29-year-old lawyer, tells me he couldn't get hired despite a law degree from the University of Chicago. So he decided to work his way through several Stanford courses on building databases while he made one for free for a not-for-profit. "I spent a lot of time trying to teach myself out of books," he says. "Sometimes when you're trying to do an exercise, you don't know: Am I not smart enough, or is it just too hard for me right now?" At Coursera, the level of difficulty was right, so he kept pushing himself. He also tapped fellow students in the forums when he was stuck. About a year and a half after he started his self-learning campaign, the political news blog Talking Points Memo hired him as a programmer. As Cahillane puts it, "In my job interview, I don't think it was, 'Oh, you took the class, you get the job.' It was more that I'd learned enough to have a conversation with a real programmer and seem like I knew what I was talking about."

Cahillane says he intends to work his way through Coursera until he's earned "the equivalent of a BA in computer science from Stanford." And this casually expressed notion--that an employed programmer now thinks he can earn for free the equivalent of a bachelor's degree, for which Stanford charges $41,000 per year--explains why free and open online learning spells turmoil for academia, with traditional educators left to grapple with conflicting impulses: to protect their turf, to get a piece of the action, to use the technology to make campus teaching better. How they participate, and to what degree they give online education their imprimatur, are questions with enormous implications.

For it's not just Ng, Koller, and a handful of VCs who think online education will cause dislocation. To Barbara Chow, education program director at the Hewlett Foundation, Coursera and its ilk are essentially moving free and open online educational resources "from a side to a central aspect in the transformation of higher education." Starting with MIT's OpenCourseware in 2001, universities have increasingly seen the provision of such resources as an essential part of their public mission. Indeed, hundreds of millions of people have viewed lectures from top universities for free online in the past 10 years. But until now, these resources have been passive, like Wikipedia. They haven't been organized and sequenced for active learning or paired with social media tools. More crucially, they haven't been offered with certification. That's beginning to change, says Chow, as for the first time traditional universities offering online courses will certify that students have mastered the contents.

At issue now is how Coursera and the established schools that are providing its content can continue to work in harmony if the schools see Coursera as eroding their existing business model. Today, Ng and Koller are free to emphasize the goals they have in common with their university partners. But once they need to make money, they'll inevitably be competing with those collaborators. Much the same has happened in journalism, when content produced by old institutions with lots of skilled labor and infrastructure was offered in a new, digital format for free, undercutting the value of the original product.

Universities, like newspapers, may feel this is a trend they can't resist, and one that might even improve the way they do their job. University of Michigan vice provost Martha Pollack, who is coordinating that school's partnership with Coursera, sees the platform as a way to "flip the classroom"--making students at the university responsible for viewing all lectures as well as completing quizzes and homework on their own time. The change would free up the in-person classroom for projects, discussions, field trips, and other interactive learning. "In the 21st century, students need to be grappling hands-on with real-world problems," she says. "Pure knowledge transfer isn't the main thing we need to do in universities."

"IN MY JOB INTERVIEW, I DON'T THINK IT WAS, 'OH, YOU TOOK THE CLASS, YOU GET THE JOB.' IT WAS MORE THAT I'D LEARNED ENOUGH TO HAVE A CONVERSATION AND SEEM LIKE I KNEW WHAT I WAS TALKING ABOUT."

The belief is also growing in traditional academic circles that online education--especially the data and insights it can generate--has a vast potential to improve teaching and learning. When a student takes a Coursera class, the system tracks the learner's every move, which Koller calls an unprecedented opportunity to understand human learning. The typical educational study has 20 students; the big ones have 200. "Here we have 20,000, or even 200,000," she says, "and it just completely changes your ability to extract meaningful conclusions from the data. We can see every single click: pausing, rewinding, the first and second try on the homework, what they did in between." In the student forum for Ng's machine-learning class, they found that a particular post helped a lot of students find the correct response to a question on one of the quizzes. In the next round of the course, Ng might include that information in an FAQ or address it directly on the video.

Whatever the potential benefits of Coursera's trove of data, universities may at some point lose enthusiasm for subsidizing the creation of a "mainstream educational provider" that relies on their own prestige and professors. Koller points out that the letters issued to those who successfully completed the machine-learning course were careful to mention Stanford only in the negative--as in "this is not Stanford credit." Administrators were very quick to make the same point to me. At Princeton, Dean Clayton Marsh mentioned three times in a 20-minute interview that they were not planning on issuing any type of credentials.

Which is not to say that universities are above profiting from online courses any more than Coursera is. How to make the transition to moneymaking is a different challenge for each party--for universities to charge for something from which they keep a certain distance and for Coursera to impose fees for what is now free. One obvious business model for Coursera and its university partners (cited by Scott Sandell) would be to charge online students for a certified copy of that noncredit letter--say, $30 to $80 a pop. Essentially, they would be introducing a "freemium" model for the world's top universities: Enjoy the courses for free, but pay a little bit for proof that you took one. And like other freemium models, only a small fraction of those who sign up need to pay in order for the business to work.

Coursera competitor Sebastian Thrun, also a Stanford professor, has mentioned job placement as another potential source of revenue. Because online teaching platforms can gather so much data about learners, a company could hypercustomize its recruitment searches--to find, say, a Python programmer who can learn new languages quickly and is good at answering classmates' questions in forums. The economics of such matching could be compelling. These days, headhunters in Silicon Valley charge as much as 20% of an engineer's starting salary, or $15,000 per successful match.

But perhaps the most striking element of any conversation about business models with Ng and Koller is that they don't seem too worried about putting one in place, even as they hire one new person a week. "Our investors are expecting us to change the world," says Koller. "What you learn from sites like Facebook and Zynga is that if people want to go there, revenue will be found." Sandell, the VC, echoes this belief. "Sooner or later, you'll figure out a business, but don't worry too much about that at the beginning."

The students are certainly there. The world's top 20 universities collectively enroll only about 200,000 undergraduates. There are, conservatively, many millions more who could participate in classwork at the highest level, and most of them are far from any of the world's leading universities. "Let's say you're stuck at some no-name state college in the Midwest," says Koller. "Now the top 10% of students at that school have the option to take a Coursera course that could open a door to being employed at companies like Google." Or think of all those who already have a degree yet need to change careers or update their skills, which is pretty much every member of the educated workforce these days.

For universities, the greatest economic boon of online education may lie in driving down the costs of on-campus teaching. A local institution, lacking its own star professors, could use its resources to guide, motivate, and support students while they make their way through the free curriculum. The University of Helsinki, Finland, announced in May that it will award credit to all students who take Coursera's human-computer-interaction course. And as state education budgets fall, an option that improves access for all at lower cost is pretty appealing. "Does it really make sense to have thousands of community-college instructors developing the same courses?" asks Koller. "We see this as an easy, very natural direction for the world to take."

The most tantalizing promise of a company like Coursera is the role it might play in improving education for the world's have-nots: high-school dropouts, the global poor, those less able to self-teach. Koller tells me that in April, only four months after Coursera went live with its first official classes, total registration hit 1 million. Christos Porios was one of those registrants; he has signed up for classes in natural-language processing, algorithms, and software as a service. "The situation in Greece, it practically destroys any hope the younger generation might have for a future in our own country," Porios says. "We will probably soon experience another emigration wave, similar to the one we saw 50 to 60 years ago." His hope is to someday study computer science in Germany or England. He is even toying with the idea of taking classes at MIT or Stanford.

But this time in person.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário